Smithsonian Museum scans a Mammoth in 3D

One of the world’s largest museums has launched an ambitious project to 3D scan its collection.

America’s prestigious Smithsonian museum is using the revolutionary technology to document its artefacts but also to share them through 3D printers and online.

3D scanning bounces lasers off objects using the echo to map them in space.

The process is used to build up 3D digital images of almost anything, regardless of size or complexity.

Adam Metello, 3D digitisation programme officer, demonstrated the technology in action.

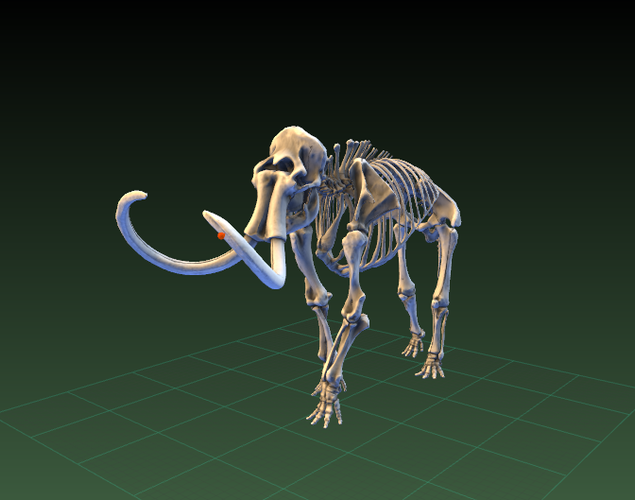

3D image of a mammoth

He used a laser gun, mounted on an articulated arm, and manually scanned the surface of an Osage Indian face mask.

“As I’m painting the laser across the surface it’s picking up hundreds and hundreds of points, soon to be thousands and thousands of points, of measurements of the surface of this object,” he said.

The Smithsonian has now 3D scanned a mammoth skeleton, the Wright Brother’s aircraft, an entire dinosaur exhibit hall and several fossilised whales.

The technology has multiple uses, not least virtually transporting exhibits to the homes of millions around the world.

Mr Metello says it makes the collection accessible in an almost real way.

“The vast majority of the United States, let alone the rest of the world, don’t get to actually come to our museums,” he said.

“So by digitising them in this way, and making our models available in a very visceral way, we can share our collections almost as if people could come to the museums themselves.”

The scans are used to create 3D images now available online on any web browser.

Any computer user can then examine exhibits almost as if they were in their own hands, like this face mask of former US president Abraham Lincoln.

Scanning the 1903 Wright Flyer has allowed the team to give people at home more intimate access to the aircraft than they could enjoy in the museum.

The Smithsonian 3D explorer can be used on any web browser letting anyone with a PC to zoom in on the Flyer and move it around.

“What we have is an ability to take that 3D scan and show the world and let them interact with that data in really interesting ways,” the Smithsonian’s Vincent Rossi said.

“You can spin the object around, obviously you couldn’t do that if you were in the museum.”

Combined with 3D printers the 3D scans can be used to create copies of museum exhibits.

A 3D model of the Lincoln mask for instance takes a few hours for a consumer level 3D printer to produce.

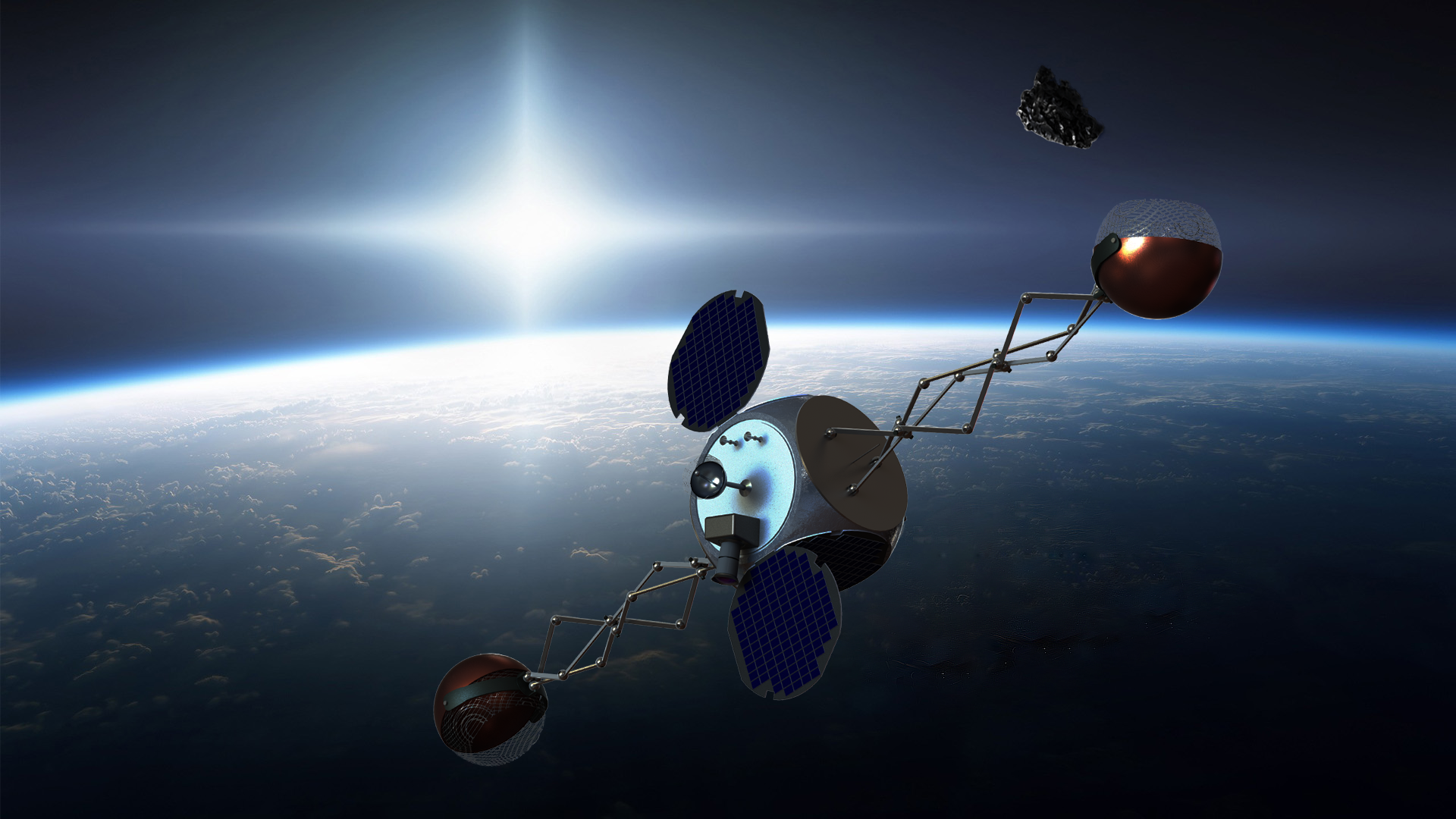

3D images of whale skeletons found in Chile

3D printers create copies of objects by printing one layer of melted plastic on top of another, incrementally building up a 3D duplicate.

Mr Rossi explained: “The 3D printing software will take that 3D model’s hundreds of thousands of 2D slices and it will deposit layer upon layer upon layer.

“It’ll actually grow the model to the point where you have the complete object coming out of your printer.”

Of equal importance is the potential for documenting discoveries in situ.

When the Pan American highway was being widened in Chile, 40 fossilised whale skeletons, five million years old, turned up.

The team flew out to scan the best preserved eight skeletons, before they had to be moved so that bulldozers could start work.

“This represents a completely new way of documenting archaeological or paleontological sites,” Mr Rossi said.

“What we have is this record of a moment in time that no longer exists, and we have a very accurate 3D record.”

The team predicts that 3D scanning a discovery before it’s removed will become standard practice, preserving its record and allowing scientists around the world to carry out research remotely.

Back home they have begun the enormous task of scanning the Smithsonian collection.

Twenty artefacts have been scanned so far, to explore the possibilities and potential applications.

There are another 137 million to go.